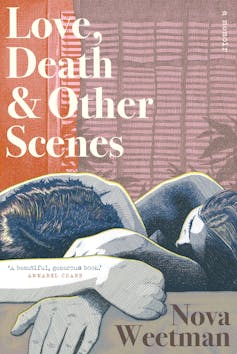

Nova Weetman’s memoir of losing her partner to cancer during COVID lockdown blends hard-won wisdom with pure nostalgic joy

Edwina Preston, The University of Melbourne

It’s difficult to critique a memoir. How do you critique the work – its language, structure, craft – without feeling you are exposing the author’s life and experiences to critique?

In Melbourne writer Nova Weetman’s Love, Death and Other Scenes, this is particularly difficult. She is writing about losing her much-loved partner of more than 20 years and father of her two children, playwright Aidan Fennessy, to cancer during COVID lockdown in 2020.

It’s also difficult, for me, because many of the experiences Weetman relates are experiences that have also been mine. Nursing a partner through grave illness (though fortunately for me, back to health again). The fear and uncertainty of diagnosis and treatment. And finding oneself middle-aged and alone, with children on the cusp of adulthood and an anticipated future life of companionship upturned.

Reading Weetman’s memoir was an experience shot through with grief for me. So I feel ill-equipped to critique it, except from this place of shared loss.

Weetman, the author of several books for young adults and children, writes of loss with delicacy, honesty and unguardedness. Love, Death and Other Scenes is a generous and open book that neither shies away from the realities and indignities of death and decline, nor indulges in unnecessary detail about them. This is not grief porn.

She writes graciously about the difficulty of living with a dying loved one — and with the omnipresent spectre of death — and not forgetting that person is still alive, and you are alive, and the world around you is alive.

For her and her children, the door to Aidan’s sickroom becomes the threshold between healthy bodies and future possibilities. There, he drinks his countless cups of coffee and, as his illness progresses, becomes a different man: a man for whom merely putting on pyjama pants is a painful ordeal.

Philosophical balm and creative vitality

Because Fennessy’s illness and death took place during Melbourne’s long COVID lockdown, the experience is particularly close and closed-off: the family’s vital, busy world becomes an insular one, leavened by the regular dropping-off of gifts and pre-cooked meals from friends.

The children, and Weetman herself, become briefly obsessed with a Nintendo game in which characters can “die daily” and come back to life, a curious and unexpected preparation for what is to come. Who could have thought a Nintendo game might provide philosophical balm in the face of death?

Weetman gently shepherds her children through the loss of their father, with care and a generosity that comes from a place of love and not mere consolation. A piano for her daughter’s 18th birthday. A new apartment which, for the first time, they own rather than rent (and the anxious reality of housing precarity for a newly single middle-aged woman is not passed over here).

Her memoir is also clearly a paean to Fennessy, even while it inventories his decline and the degrading ways his illness impacts his body. His plays, especially his last play The Architect, feature as ways in to his interior experience of illness and mortality.

They also provide a sense of his creative vitality, and of the sparring, loving and mutually creative relationship shared by the couple. Weetman and Fennessey’s writing lives, though not intersecting, were certainly informed by each other.

It’s also a book about the loss of youth and what might, unexpectedly and sometimes joyfully, arrive in its place. Weetman refers to herself as a “grass spinster” — an old term derived from the German “straw spinster” — which came to mean a woman who is widowed without ever having been married. (Weetman and Fennessey were not married.) She notes the newness and freshness of the term: grass is alive and growing, of this world, not (like straw) a dry, brittle reminder of what once was animate and is now a mere remnant of life.

But she feels more “partnerless” than “single”: unmoored and unanchored. And while “single” contains a ring of opportunity, “partnerlessness” denotes absence, a void where there might be a meaningful “other”.

Weetman is still grappling with this void, but is planting small stones in a new and different pathway for herself: other older single women she meets in her new apartment block, who are living rich and fulfilling lives, small outings with friends and the comfort of pets – even a pet that doesn’t seem much to like her.

Moments of pure nostalgic joy

While Love, Death and Other Scenes germinated as a way to process her loss, Weetman does not only give us loss – her book is threaded through with promise and hope. She experiences the twinges and mirror evidence of ageing in her body, as well as flashes of her own mother’s physical decline, but takes control by joining a gym: a regime of bench-presses and dead-lifts surprises her with the emergence of unexpected bicep muscles. When her body hurts now, it is due to exercise, not age.

Love, Death and Other Scenes also glints with shards of memory for Generation X readers: of the grittily hopeful ‘90s, when Weetman came of age, clinging to her copy of Sylvia Plath. Of the ’80s, singing to Morrissey and discovering the books of Peter Carey. Of the ’70s, eating chocolate mousse straight from the fridge and chancing on “intact After Dinner Mints in their slips of black paper”.

There are moments of pure nostalgic joy here, which cause Weetman (and me) not to lament the passing of youth, so much as to feel blessed for growing up when we did: in times when it was possible to be an artist on the dole, sharing a house and a diet of kidney bean stew, and still feel you were living a good life.

I’ve heard the ’90s described recently as a political hiatus between the end of the Cold War and the 9/11 attacks. The enormous challenges of the present, though on the horizon, did not pierce consciousness in the way they do for 20-somethings now.

If the 90s was an act between acts, in Love, Death and other Scenes, Weetman finds herself in another such act. Towards the end of the play, perhaps, and possessing wisdom gained through hard experience, but also with an appreciation that plenty more is to come.

Edwina Preston, PhD Candidate, School of Culture and Communication, The University of Melbourne